|

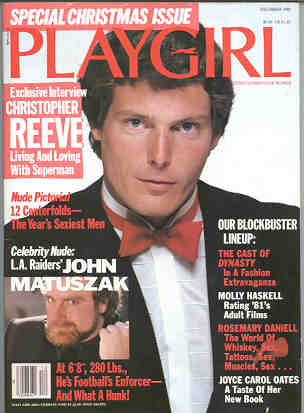

Playgirl - December 1982Exclusive Interview by Henry SchipperCHRISTOPHER REEVE SUPERMAN AND CHRISTOPHER REEVE DO NOT HAVE very much in common, despite the fact that they probably will be forever linked in the public mind.

SUPERMAN AND CHRISTOPHER REEVE DO NOT HAVE very much in common, despite the fact that they probably will be forever linked in the public mind.Physically, the resemblance is surprisingly superficial. A gangling six feet four inches and 188 pounds when he got the part, Reeve had to work out full-time for six weeks, lifting weights and eating massive starch and protein meals in order to develop a physique that would enable him to pass the Man of Steel. Clotheswise, the two couldn't be further apart. It's hard to imagine Superman as a preppie, but that's the look Reeve enjoys, wearing loose-fitting khaki slacks and pullover vest for our interview, an outfit so plain and conservative as to suggest that, even if Reeve were Superman, he would never deck himself out in anything so risque as blue leotards and a red cape. But the real difference between character and actor comes through when Reeve begins to speak. Only then is it apparent that, in playing Superman, Reeve is playing against type. For part of the charm of Reeve's Superman, despite his ability to outrace a speeding bullet, lies in his watchful, wondering, vulnerable absorption of life on the alien planet Earth, which is more affecting that his mighty miracles of action. His pride is gentle and measured, the pride of a caring superhero who knows that his powers are surpassed only by his responsibilities. By comparison, Reeve seems almost flinty and hyper. His eyeballs pinpoint and peck as he speaks, and his speech itself borders on the hectic, his words like pellets knocking down the targets of his ideas. He pursues a line of thought with an almost peremptory intensity, which would be an interviewer's delight were it not for the angry air of threat that goes along with it, a warning against broaching subjects deemed too personal or against milking the obvious Superman angle to excess. For much of the interview, Reeve seemed poised and on edge against any such intrusions or blunders, talking about Superman with curt impatience, and about his private love and life guardedly, when at all. Here at least we discover something Reeve has in common with Superman: a secret identity he feels he must protect, not against villains like Lex Luthor, who would take his loved ones hostage if he could, but against the media machinery that would grind the stuff of his intimate relationships and experience into grist for the tabloid mill if he let them. Reeve says as much himself. "I've learned how to be defensive with the press," he admits. "As you see yourself getting minimized, packaged into a four-minute segment on the news, you begin to resist, like a Christmas present that doesn't want to be. You gave to say no." Certainly Reeve would have grounds for resenting attempts to gift wrap him as Superman for the rest of his life. A veteran of some 90 stage productions, he began acting when he was nine years old, paying apprenticeship dues at summer-stock theaters in New England and New Jersey, where he grew up; studying at Juilliard, where he chummed around with Robin Williams; starring in the soap opera Love of Life to pay his tuition; and even appearing on Broadway opposite Katharine Hepburn in a 1976 production of A Matter of Gravity. All this before getting his film break in 1978 in Superman. It hardly seemed like a superbreak at the time, given Reeve's Ivy League background and his higher ambitions to do "serious" acting. (His father, F.D. Reeve, is a noted Russian translator and professor of creative writing at Yale and Wesleyan; Reeve himself is a graduate from Cornell.) Indeed, Reeve's decision to accept the comic-book hero role left family and friends mildly appalled, especially his father, who assumed his son had been cast in Man and Superman, a play by George Bernard Shaw, when Reeve first called to break the news. "He asked me who got the part of Ann, the female lead in Shaw's play," Reeve recalls. "I told him there was no Ann, only Lois. There was a long pause. 'Oh.' he finally said. 'You mean you're going to play that Superman.'" Indeed he was, and more than once. Superman III, in which our hero returns to his hometown for a high school reunion and swoons over his childhood flame Lana Lang (Annette O'Toole), is already in the can, and through Reeve says that will probably by the end of it, he has left the door open for additional sequels if the script is right. Reeve can't really complain about being pigeonholed by the role, not as far as Hollywood producers are concerned anyway. Since the first Superman, he has enjoyed the most varied set of screen credits this side of Robert De Niro. In Somewhere In Time (1980), he is a love-entranced writer who wills himself into nineteenth century in pursuit of the girl of his dreams. In Deathtrap (1982) he is Clifford, a gay hunk involved in a deadly psycho-battle with lover Michael Caine. And in Monsignor, Reeve's latest film, he plays a Vatican-based cardinal who operates as a Mafia-backed industrialist on the side. So much for superhero typecasting. In his personal life as well, Reeve hardly seems circumscribed by the Superman image. He lives in a co-op apartment in New York's upper west side with British-born models' agent Gae Exton, who he met on the London set of Superman in 1978. They have no plans for marriage, despite the birth of three years ago of a son named Matthew and current rumors of another child on the way. Last spring, on the day before we met, Reeve was in the news for having participated in a series of demonstrations protesting the demolition of Broadway's Helen Hayes Theatre and Morosco Theatre. The rallies were a result of an unsuccessful last-minute Supreme Court appeal to halt the demolition. Although many well-known actors and actresses were arrested-including Richard Gere, Tammy Grimes, Estelle Parsons and Michael Moriarty-during the protests for refusing the vacate the site, Reeve, somewhat conspicuously, was not. It seemed like a good subject on which to open the interview, and I began by asking Reeve if he had intentionally avoided arrest and if so, why. Reeve: I'm a practical man. Once the Supreme Court said no, then that was the end. I didn't see the point in breaking the law. This is my personal view. I completely support the other people who made that gesture, but I just felt, "Hey, we lost this one gang, we have to move on." Not that there aren't some situations where I think it's valid to break the law, like the Vietnam war. That was a big, covert, illegal military operation, and people therefore had a right to protest illegally. But what was the point of getting arrested for the theaters? The point was to generate publicity, and while everyone else was getting arrested, I was able to do two- and three-minute interviews with every network. Playgirl: Right, but it was the arrests that brought the networks out. Reeve: We needed some people to get arrested, but we needed people to talk with the media too, to explain why the others were getting arrested. As I said to Dan Rather, people in this country better know what they want, because they just might get it. If we want cities of steel and glass and fast-food chains and television, we'll get that. We'll get nondescript, efficient city centers with no soul, which will reflect our deterioration as a culture. I wanted to say that, and I felt I could say it better by talking than by being marched away in a line. Playgirl: Did the idea of Superman getting arrested, and the damage that might do to his image, inhibit you at all? Reeve: Not at all. The first day of the protest I said this was one time I wished I were Superman so that I could just catch the wrecking ball. Playgirl: That's a fantasy that must come to mind in more than a few situations. Reeve: Not really. I'm a realist. I want to know what you can actually do in the real world to solve real problems, and Superman jokes don't solve anything. Superman jokes are for people's entertainment, for fun, and I crack those jokes about myself frequently when I feel like it. But the theater question is a very emotional one for me. I grew up in the theater, I began there, and losing the Morosco and the Helen Hayes was like losing a brother to me. When I was 14 years old, or maybe younger than that, I used to come to see plays on Broadway, used to walk down the theater district hoping that one day I'd be in a play there. That was the dream. That was magic for me. When they tear down the theaters it's a reminder that we're a very rich culture and also a very poor one. We have material things but we have very little spiritual and cultural life. And we have very little respect for our past, for the people and traditions that came before us. The theaters are just another disposable consumer product, and that disrespect for and loss of our heritage is sad. Now in place of the Morosco and Helen Hayes we're going to get a 1,200-seat theater like the Uris or the Minskoff, where you have to have a Pirates of Penzance or a Chorus Line to fill it up, and then you have out-of-state people on business accounts going to see nonprovocative commercial theater, and it's another stab in the back to the legitimate theater on Broadway. Playgirl: Can you elaborate on the negative landscape you sense for this country in terms of culture? Reeve: The negative landscape, one we are really in danger of developing, is a landscape for rich people that leaves aside poor people, who are already being wiped out by Reagan. It's a landscape for people who can afford $38 and $42 tickets: for 31-year-old account executives who have a Jacuzzi and a Porsche and take vacations in the south of France, and the only kind of theater they can handle is Dream Girls or 42nd Street, where you come out with nothing more than you went in with. It's a world where the computer triumphs and Atari TV games flourish; where people stop talking to each other, vocabulary diminishes; where people's attention spans are minimized by the evening news; where they stop imagining and conceptualizing and take their perceptions of the world literally off the TV screen or from dramatic material that poses no challenge. We will be rich people with no soul, comfortable and efficient but with no real life. That's what I see. Playgirl: What about poor people? What do you see for them? Reeve: I think Reagan is absolutely raping poor people in this country. He's frightening. His basic policy as I understand it is to give money back to big business so that they can reinvest it and it will filter down. The amount of time that that takes is something I don't think he understands at all. Not to mention the damage he's doing by the defense buildup. He's got his priorities totally screwed up as to what this country needs and wants. Cost overruns for military band uniforms exceed the arts budget! I think that's true. Certainly the cost of half a submarine is more than the entire arts budget. I just don't think Reagan knows what he's doing. I don't think he has a clue. He's provoking the Russians in a terrifying way. It seems to come for some sort of misplaced pioneer spirit. You know, "By God, we're gonna make it across the Cumberland Gap." What Reagan seems to dig into is this thing of believing in himself no matter what his critics say, which I think is a particularly American trait. But with any luck the eighties will be the end of the "me generation." People will become alive and active again and unwilling to live with mad defense policies-like the one we have now with The Bomb hanging over our heads. Hopefully, people are getting tired of being victims. Playgirl: Would you support a unilateral nuclear freeze? Reeve: Absolutely. I would lead the movement toward it. In fact, I plan to be helpful in that way. Playgirl: Do you have any problems with Superman's politics, his role as a defender of Truth, Justice, and the American Way? Reeve: The way I deal with that is to dismiss it completely. I refuse to entertain, even for fun, the possibility that Superman has anything to do with the real world. Really. Superman is enjoyable popcorn entertainment, and I cannot grant him any more important status than that. Playgirl: Don't you think he has any influence on the way kids see the world? Reeve: I certainly hope not. The only way I would want Superman to have an influence is as a gentleman. I think that's important. The whole heroics-the stopping of bullets and fixing of bridges-bore the shit out of me. But he's a gentleman, he's a Sir Walter Raleigh. He cares more about people than they will ever know. And if people take inspiration from that, that's fine. But I wince at the idea that he represents anything else. Playgirl: Aren't you blinding yourself? Reeve: Yes. I know he's been around for 50 years and has been read and absorbed by everybody, but I just can't get involved in that. There's also the real world and I deny that a comic-book character has any place there. I don't care if Superman did sell war bonds in the forties, it doesn't interest me in the least. I'm not interested in speculating on the psychology of why Superman was created or what he means to the world. I get letters from people who want me to appreciate the religious overtones-that Jor-El made Kal-El and sent him to earth, where he grew up and found his authentic possibilities....I find that to be treacherous ground. It's pop psychology and I think it's dangerous. Playgirl: What's the distinction you make then between someone like Superman and a character out of Chekov, in terms of their potential impact? Reeve: Chekhov creates no symbol that you can identify with for 10 cents. Playgirl: Nicely put. You are signed up for Superman III, are you not Reeve: Yeah, I signed back in '79 for that. Playgirl: Will that be the end of Superman? Reeve: Yes for me. Playgirl: Absolutely? Reeve: Yeah, I don't know....Unless they come up with a really great idea. But if someone said, "For 10 million dollars, you'll love it," I'd say no. I've never done a project for money; that is for money alone. I have no objections to making money, but I don't do work because I have a house with a pool and I have to pay for it. If there's nothing you really want to do, move out of the house. No one says you have to have a swimming pool. I think when you start working for money you turn a corner. It's a violation, really- Playgirl: Of what? Reeve: Of you integrity. You've got very few things that are private in this life. You've got your pride and your self, and those are the last things you can sell. You can sell sex, you can sell your secrets-how you run around the house, make love swinging from the chandeliers. People do that regularly. One of the few things you have to hang onto is your integrity about your work, and I think work defines a great deal of who you are. If you don't have any pride in your work, then I wonder, who are you? Playgirl: Do you think that pride is enough to give a person the balance necessary to survive in your business? I'm thinking of John Belushi. Reeve: It can help you like yourself. You can go through bad times and everything might fall apart, but you'll still like yourself. I'm not saying I've got a great plan or that my movies are all so wonderful, just that I never work with that cynical detachment of not giving a shit, which a lot of people do. Playgirl: You attended Belushi's funeral. What did his death put you through? Reeve: His death made me angry. The first thing you wanted to do was grab him and punch him in the face and say, "You stupid jerk!" Then later you felt compassion for a man who wasn't happy, who burned himself out. He lived his life in a hysterical way to avoid really thinking about who he was. A lot of people do that. Motion becomes its own end: "Keep moving, you don't have to think about it, keep it going." Playgirl: There's also the tease of being on the edge, the payoff of staying fresh and seeing things with a special keenness by risking yourself. Reeve: The danger is, when do you stop? That kind of pain comes out of the fact that you no longer respect yourself. Why do you no longer respect yourself? Because people respect you too easily. And you know you're not that good. That was the bottom line, I think, for Belushi-he knew he wasn't that good. He was good, he was funny, but he never intended to be a spokesman for his generation, which is the way he's been eulogized. Actually, he hated people who liked him. If you fawned all over him, he'd walk away from you. Playgirl: What's the history of your friendship with him? Reeve: We first met in '78 when Superman was just coming out and I went to a Saturday Night Live and we ended up at a club where he gave me a 10-minute lecture on the perils of fame. I don't want to reveal what he said. Playgirl: Did it prove prophetic? Reeve: Pretty much. We were friendly. I never went out raving with him, but I was one of the people he'd talk to when he wanted to sober up a bit. Playgirl: Can you talk about the different choices the two of you made with regard to where you get your creativity? Reeve: I think we were just totally different people. I don't know how I can even compare us. We weren't fueled by the same needs at all. I'm not a compulsive person. Also, I like myself. I've never been unhappy. And I don't need fame to make me happy. But that's pretty obvious. Playgirl: Do you feel there are two sources of creativity-one dark and one light? Reeve: Sometimes, yeah. Sometimes you think the really talented people are somehow out of control. That the highs are high and the lows are low and there's never a middle ground. They're either way up or way down, and this makes them brilliant. But early in my life I was associated with brilliant people who were also stable, and they impressed me. I was exposed to the likes of Robert Frost, who was a close friend of my father's. Adlai Stevenson and Robert Penn Warren would be sitting around our dinner table. These were thoughtful people, poised people. And it seemed to me that real creativity comes out of calm, comes out of an ability to really see, to really observe, and then swing into action when you're ready. Whatever I can do does not come of uncontrolled energy, but out of a kind of planned spontaneity. Playgirl: Whereas another kind of creativity is like taking a blind fall? Reeve: Yeah, let's just go out and see what happens. Katharine Hepburn introduced me to the reason why you should stay in control-particularly in comedy, where you need more discipline because it requires consistency every time you do it to get the laugh. Your partner must know how you're going to do your bits, and then he can do his bits. It's teamwork, a dance, a ballet. Strict, strict timing, like a swan-he looks smooth on top, but his little feet are kicking underneath. You are absolutely, rigidly in control. When you do comedy, be fierce with yourself. Belushi had it backwards, if you ask me. He was playing his comedy off the wall, with no discipline, no form, living his life out of control. And he was wildly erratic. His career wasn't that hot. His last two movies, Continental Divide and Neighbors, aren't major pieces of work, certainly nothing to compare with the genre of a Tracy and Hepburn. Do you know what I'm saying? But his death will glorify him, and that's sad, because it comes out he didn't like himself. A really great person, the really great ones, are generally at peace with themselves. Playgirl: What about Buster Keaton? Reeve: He was a miserable man, and as soon as you make a rule for somebody, you find an exception to it. But that's a dialogue that has to be had: Do you want to be one of the crazies out of control, sometimes brilliant, sometimes terrible? Or do you want to be somebody more dependable who has a body of consistent work that may not have the flash or the madness or even the genius, but is good in its own way? Playgirl: Do you ever use drugs to stimulate your creativity? Reeve: No. Playgirl: You've never tried to get an angle on a character by getting high? Reeve: No. I had health early on. Getting back to the people I mentioned earlier-Robert Frost, Robert Penn Warren-they impressed me as capable people who worked through strength. When you're working, you've already go the limitations of your talent to fight against, and then to further limit your talent by getting smashed- Playgirl: On the other hand, drugs can break down some constraints and pull away blinders that too narrowly control the way you see. Reeve: But I think acting through getting it together is better than acting through letting it fall apart. You can be as interesting through composure as through decomposure. Playgirl: How about living-doesn't that apply to life as well? Reeve: Yeah, somehow you work the way you live. I don't see how you can live as a pig and suddenly clean it up to act. A gradual disintegration affects both. Playgirl: So, you've never used drugs? Reeve: [Laughing] No comment. No comment. [More laughter] Playgirl: Does "no comment" have anything to do with Superman and being careful about his image? Reeve: No. Superman can live any way he wants. Playgirl: We talked earlier about politics. What about sexual politics? How would you describe yourself with regard to that? Reeve: You gotta tell me what you mean.... Playgirl: Do you identify with being macho or sexist; or with feminism? Reeve: Multiple choice-how about all of the above? Playgirl: Is that appropriate? Reeve: Is there a right answer to this question? Playgirl: Depends on who's reading. Reeve: I'm not a competitor with women. I'm not threatened by them or their success. I enjoy it. Women like Sigourney Weaver, Genevieve Bujold, Margot Kidder, Carly Simon-people with something on the ball, with lots of independence and strength-interest me a lot more than the Barbie dolls of this world. I will say that. Playgirl: In terms of relationships, though, have you been influenced at all by the women's movement? Reeve: Sure. I tend to end up with women who have something [in them] to challenge me. I'm attracted to achievers, capable people, not people who gratify me by fawning all over me. The groupies and the worshippers and sycophants I turn away from. Playgirl: In terms of the way you relate to the women who attract you, has that changed at all because of the women's movement? Reeve: No. I'm still young enough that the women's movement has always been a part of my life. And I became involved with women through theater, which was a great equalizer. It never occurred to me that there was not equality, because there were leading actresses as well as leading men. So that has always been a part of my life. I had a girlfriend in college who was not only going to become a brilliant lawyer, she also played the violin and viola and cooked the best omelet in the world. There was a mixture of everything, and roles didn't matter. It didn't matter who did what. There was no competitiveness, and I reveled in her talent. Playgirl: In your relationships then, the roles break down and become interchangeable? Reeve: Very interchangeable. I find with Gae, bringing up [son] Matthew, there was no boundaries. Whoever's nearest does what needs to be done. I must admit I was less interested in Matthew when he was very young, after the actual thrill of birth. I was less interested in the early stages when he looked like a raisin and everyone insisted he was beautiful. I was sometimes glad I had to get up early and go to work. I think an honest father would admit that-that it's not always a little miracle. But I became more interested in Matthew as he got older. Matthew reflects about willingness to share everything. It's a threesome. The identities sort of leave off and you don't really know who does what when. It's a little triangle that works, without specific corners. As a result, he's a very happy kid who's not threatened by new situations or people. That's based on security and love. Some kids have to have the door opened a certain way, or the teddy bear in the right place. Matthew loves a new deal. And the relationship [with Gae] thrives because when the roles aren't clear-cut you tune in more to the other person. Instead of, "This is your job, that's my job," you ask each other whether you're up to doing this now. You communicate with your partner instead of saying, "Diapers are your department." Playgirl: You said you first began going out with girls in high school. Were you a shy kid? Reeve: Yes. I was very tall and very awkward. I was six feet two inches by the time I was 13 and I wasn't well-coordinated. I had Osgood-Schlatter disease, which makes the tendons grow faster than the bones, so you have a lot of fluid in the joints, and you don't move terribly well. I used to stand with my legs locked all the time, and I hated dancing. The whole dating game was painful, it really was, because I was also a very serious kid, and a lot of girls weren't ready for that. Not serious about "I love you," but about World War III and the latest article in The New Statesman. I was not a whole lot of laughs. Playgirl: So girls in high school couldn't relate to you? Reeve: Never the ones I wanted. I always ended up with dates who were not quite the girls I wanted. Playgirl: Were you frustrated because you couldn't loosen up? Reeve: I could loosen up, but only when the stakes weren't very high. I could do that when I was with a girl who I knew already liked me. When the situation was in the bag. But get me around a girl I wanted to impress and I clammed up. I was really quite scared. You're so naked with the girl you really want. I didn't understand that what makes it so difficult is that there's real sexual tension. The girl is hard to talk to because she's also attracted. You can always talk to people you aren't attracted to. Or who aren't attracted to you. If you only knew that the awkwardness was desire, you could have cleaned up. Playgirl: When were you able to make that transition in your own life? Reeve: I think fame really helped me to get the ones I wanted. Playgirl: I'll bet it did. Reeve: Where were the girls when I was 18 and didn't believe in myself? They do come out of the walls. Women are attracted to power and prestige. Playgirl: Now that they were attracted it was no longer- Reeve: Now you've got them in the bag, or at least halfway there. If you had to gamble on it, the odds would be 70-30 in your favor- Playgirl: 70-30 odds you could play. Reeve: 70-30 you could play. Even 60-40. Playgirl: That's one of the great payoffs people fantasize about with fame. They believe if they had more going for them, they could blossom. Reeve: Fame also pulls out the swamp rats. Fame pulls out the people you never wanted to see in the first place, who hang after you. They aren't that bad with me though because I'm elusive. It's hard for them to catch up with me. Playgirl: What do you mean, swamp rats? Reeve: The ones who don't want to do any work, like Clifford [Reeve's character] in Deathtrap. He wants a ride on the best-dressed coattail-"I'm going with him." That equivalent. But that's what's also amazing about the blue-ribbon girl, the one you want. One of the things you prize about her is her purity. Not pure in the sense of her being a virgin and all that crap, but pure meaning moral-pure in the sense of seeing the world the way you want someone to see it, through being intellectually alive. But even with the blue-ribbon girl there is an amazing amount of willingness to climb on a bandwagon. Why is it that all the people who said you were flushing your career down the toilet came to the premiere? When it looks like someone's on a roll, almost everybody wants to get on the roll too. There are no real purists, no people who say, "Well, I was against this all along and I'm going to stay against it." Some of the girls I knew who would put down the commercial world, not wanting to be a part of it, were suddenly like relatives who laughed and jeered and then wanted to help with a book deal. Relationships go corrupt on a certain level. Levels. Playgirl: In terms of relationships, isn't something lost because of that? Reeve: Yes, you say, "Wait a minute, I've come all this way and now you're going down in my estimation. I'm just at the stage where I can have you and I don't want you so much anymore. Because you're changing on me. It's not that I'm changing. You're changing. I'm still the same person but now you're treating me differently. I can see a little spark in your eyes that you might get a ride with me someplace." Playgirl: Does that play into your relationship with Gae at all? Reeve: No, and that's why it lasts. Gae met me while I was shooting Superman, before I became famous, and she has never wavered in her appreciation of me or her criticism of me from that day to this. Her consistency makes you know there's a depth to the relationship. Whether I were to become a bricklayer tomorrow or win an Oscar, she'd still be with me. Playgirl: You're confident the relationship isn't tainted in any way? Reeve: That's right. Playgirl: Can you pinpoint what makes it work, beyond that? Reeve: Many things. First of all, relationships start in bed, right [laughing]? It starts in bed, then it moves to the living room, then to the kitchen; or maybe it goes bedroom, kitchen, and then living room or library. I like that idea. Playgirl: Feeding all the appetites. Reeve: Yes. Playgirl: When you put the bedroom first, are you saying that sexual compatibility is at the forefront? Reeve: Yes, I am. Without that, you're just good friends. You have many good friends, but I think you have only one lover, which is an intimacy with someone that depends on time and is in part defined by time. One of the dangers of becoming famous is that so much is available so easily. Not only swamp rats but....you have a hard time being vulnerable, because you have to learn to be aggressive and defensive at the same time. And aggressiveness and defensiveness are not good for your soul. They make you a winner, and a winner is not a happy person, necessarily. With Gae I get back to that prefame health. She helps simplify things for me when they become convoluted. She helps me keep my vulnerability, my awkwardness. And my sense of perspective. She reminds me that I'm working in the movies, for Christ's sake. I can break my balls doing a scene and come home and tell her and she says, "That's nice," and I go, "Yeah, that's all it is, just nice. We didn't win or lose the colonies today, we just make a movie." Playgirl: Speaking of which, you just finished shooting Monsignor, in which you play a priest. Was it difficult playing a religious role? Reeve: I was brought up Episcopalian, and I went to church mainly to try and score in the alto section. Really! What frightened me about Monsignor was that I wouldn't be able to find the religious conviction. I felt like such an imposter. It was arranged for me to learn how to perform the Mass at an actual church on 59th Street. They would close it down at eight o'clock and I would come in and put on all the vestments and perform the Mass for a priest who would sit there and take notes and grade me. I got an 8 for Latin, a 7 for altar deportment, and a 3 for holy water. During the marriage ceremony I could not make the little wrist action necessary for the blessing of the rings. Water, water everywhere. I thought, "I shouldn't be here. These people have made sacrifices, commitments, this is their life, and I'm doing it as a job." Then I got wise. A young priest helped me very much. He said, "Don't kill yourself trying to find God. Make yourself at home with the articles. Walk around the altar. Here, have a wafer." I began to relax. Gradually, I learned the exterior forms of being a priest. It was like learning dance steps. As for the deeper stuff, I didn't have any religious conviction so I decided to use something else - the feeling I get when I'm in a glider halfway over the ocean at 31,000 feet. It's a loss of self. For a moment you disappear into something you can't name. When you come out of it you don't really know where you've been but you know you've been someplace; you've transcended for a few moments. And that moment of perfection might be something like what religion is. Playgirl: So you injected that into the role? Reeve: I let it substitute. A religious person is striving to know God. The equation is that I am trying to reexperience those moments of fulfillment, because God is fulfillment. Playgirl: So when we see you in Monsignor getting ordained as a priest- Reeve: I've gone gliding....

Movie Reviews | Contact Info | Have Your Say | Photo Gallery | Song Lyrics Transcripts | Mailing Lists | Interviews | Other Websites | About Us | Search

|