|

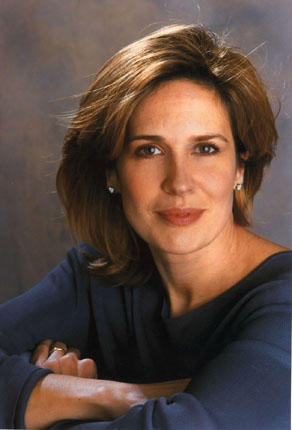

Dana Reeve AccessLife.com 2000 Caregiving Opinion ColumnEyes of children bring clarity By DANA REEVE

By DANA REEVEFor AccessLife.com (Posted June 30, 2000) I sit here on a rainy Father's Day contemplating a topic for my first article. I have been asked to submit a monthly essay on caregiving - or overcoming adversity - or the triumph of the human spirit - or any number of subjects for which my situation and my husband's should make me eminently qualified. Five years ago, my husband was rendered quite suddenly a ventilator-dependent quadriplegic and his children and I, just as suddenly became his support system, allies, and caregivers. I know that quite often we provide the reason why he can face each day with a positive outlook despite his severe limitations.

Family unity Living with my husband's disability for five years and counting, we are doing quite well and should have a number of insights to share. What I am struck by, however, is how hard it is to encapsulate our experience in any way that might be useful to anyone else. So, on this gray and drizzly Father's Day, I find myself looking back to the beginning of this particular journey in our life, to a time when who my husband was as a father was being both challenged and redefined. And as is so often the case in our life, it is our children and their insights that bring us to a point of clarity and understanding and guide us toward hope for the future. In that light, I share with you a story. It took a week before Will could muster up the courage to walk down the corridor of 6 West -- a wing in the UVA Medical Center that was serving as our home away from home - and actually enter Chris's room in the Intensive Care Unit. The last time Will had seen him, Chris was lying on a gurney, intubated with bright caution-yellow wedges of foam stabilizing his broken neck, while the medevac helicopter waiting to take him away rumbled and whirred outside. Will had been frightened by what he saw, and I'm sure the image of his dad lying there unable to answer his questions lingered in his mind and haunted his imagination. Matthew and Alexandra, Chris's two older children, had flown in from England with their mother and spent many hours a day with Chris -- swabbing his mouth with small sponges that provided moisture and, later, when he was more fully conscious, talking to him, reading to him, kissing and hugging him. But Will, not quite 3, like most children his age, probably thought that what happened to Daddy might happen to him if he ventured too close. So he kept his distance, listening intently to others reporting on Chris's progress, monitoring the gradually improving moods of family members. He processed the events that had occurred by acting out Chris's accident over and over on the hobbyhorse in the pediatrics playroom -- his own self-initiated play therapy. He would fall off the horse in slow motion, calling out, "My neck! My neck!" and I would reassure him that his neck was fine, but Daddy's was injured and made it so he couldn't move. On the day Will finally entered his father's room, Chris was wide awake, smiling, and ready to make entertaining faces. He couldn't sit up because his head was in traction and he couldn't speak due to the snugness of his newly inserted trachea tube, yet he was clearly the same Daddy in many other ways that Will recognized and loved. We kept the first visit fairly brief with lots of snuggling; Will chattered away about the freight trains that went by periodically outside the hospital lounge windows and the games he played with Susan and David, two kind nurses who had taken Will under their wings. (Later in the month, they would organize a little birthday party for him, complete with rubber-glove balloons and a tiny pair of scrubs gift wrapped with a festive bow made from burn gauze.) I could see the fear melt away from Will's face as he positioned himself in the crook of Chris's motionless arm and his knobby knees resting on his daddy's belly. We left the unit ebullient after our visit, fairly skipping past other families and other visitors who waited with familiar numb expressions brought on by worry and sleeplessness. I recognized those faces. I was one of them, on another day, perhaps. But not today. Will's overcoming of his fear had imbued him with a newfound courage. His visit reminded Chris that his children -- all of them -- needed him, loved him and delighted in him, whatever the circumstances. And I was awash in the welcome, warm glow of hope. Will became a regular fixture in the ICU after that, learning the rules, which were strict by necessity, and befriending the hard working, dedicated nurses. On one particular day, a short time after his first breakthrough visit, Will sat near me on the floor of the mail room eating a small cupful or orange sherbet. The frozen treat, usually reserved for tonsillectomy patients, had been slipped to him by a newly acquired nurse friend. "Mommy," Will said between bites of sherbet, "Daddy can't run around anymore." "No," I replied simply. "Daddy can't run around anymore." "And Daddy can't move his arms." "No, he can't move his arms." "And he can't talk." "No. That's right -- he isn't able to talk right now." Will paused, sucked on the flat wooden spoon, his face puckered in concentration. And then, suddenly, brightly: "But he can still smile!" And these are, I think, the gifts that children bring to us if we let them: hope, unadulterated love, immense courage, and the potential through any kind of hardship to still smile. It has now stopped raining. And everything is much, much clearer. How fitting.

Family finds challenges and joy in daily lifeBy DANA REEVEFor AccessLife.com (Posted Sept. 8, 2000) One of the greatest things I aspire to is a sense of normalcy. Now, this may not seem like a tremendous achievement, but in a family such as ours, normalcy is a rare and wonderful commodity. Life with a disability, no matter how well you've adapted or how active you are able to be, is -- and there's simply no politically correct way to say this -- well, different. Now, different is not necessarily bad, but different can be challenging, frustrating or isolating.

Obstacles can be emotional, spiritual or physical It may be spiritual, as in the awareness that by continually trying to create something good out of our hardship we are actually bringing purpose to what could be considered a tragedy. Or the obstacle may be physical, as in the 697 physical obstacles that present themselves daily and need to be attacked and conquered head on. As mundane as those physical obstacles can be, however, overcoming them can sometimes bring the deepest satisfaction. Life becomes one big "to-do" list. And with every task that is checked off the list -- get Chris dressed, get him out of bed, eat breakfast, talk on the phone -- another step is taken towards normalcy. Going to the movies or hanging out in the park to watch our son's ball game or eating in a restaurant are terrific treats, not only because they are enjoyable activities in and of themselves but because they provide us with the feeling that we are just like everyone else.

We are normal Yes, we have to make sure Chris' temperature is kept down to human levels by continually spraying him with cold water at the ballpark. And yes, we must call ahead to the restaurant to make sure that "ground level" doesn't mean "just one small step" and that the manager understands that what he calls a "threshold" could actually be the 3 1/2 inches that prevent our eating that evening. And when we grab the parking spot, keep Chris comfortable or get to our table without a hitch, we have really done something. Despite all the odds against us, we have reached the pinnacle of normal. And it feels good. That's not to say the obstacles don't keep coming, because they do, or that they are not immensely frustrating at times, because they are. It can be particularly annoying when the very things meant to make your life easier actually create greater chaos.

Expect chaos with the ease If you've ever had to rent a wheelchair-accessible van you know that a) it's almost impossible to rent one last-minute for a holiday and b) even if you could, there's nobody there to answer the phone anyway because they are enjoying the holiday. If by some miracle you do manage to find someone who actually has a van in stock, it's probably in a town 50 miles away and they won't deliver … because it's a holiday. So you find a ride, bring the van back home, and then the fun really begins. Recently we had to rent a van because our #*%! * lift broke for the #$%^* 20th time. We sent one of our incredibly dedicated and hard-working aides to pick up a rental in Queens … about 50 miles away. When the van pulled into our driveway, it looked innocent enough, but we would soon discover that it was, in fact, possessed by the devil. Every knob we touched seemed to fall off in our hands. That's OK, we think, we love fresh air. The radio was jammed onto a station that only played muzac. OK, so we won't listen to music, we'll enjoy the lost art of conversation. (Sure, that would be fine if we could hear ourselves over the sound of the rushing wind coming through the perpetually opened windows.) Everything will be fine, I mean, at least we have a van. At least we can go to the party all our friends are attending. At least we won't be isolated, alone, ostracized for having a disability.

At least we have a van or so we thought

We are always very careful to point this out to places that may be renting us a van, lest they think we can load Chris into a van with an inferior lift. The lift must be capable of hoisting up more than 500 pounds of very precious cargo. Having made our point several times, we trust that this lift and this van are up to the task. This is our first mistake. The lift doesn't completely fail. Not at first, anyway. The front lip of the lift just doesn't look right. It doesn't seem to be up fully. (When we asked for a disabled van, we didn't mean the van itself should be disabled.) But, that's OK. We'll just keep an eye on it. As long as the lift goes up and we get Chris safely into the van. When the lift starts to shake violently as it rises, the "safely" part of the operation seems to be somewhat in question, but we surge ahead, being now halfway up. It is not until the angle of the lift begins to resemble the slope of an Olympic ski run that we realize we must abort. But now the lift won't go up or down. Chris is stuck. Not to worry, not to worry -- we'll simply "go manual." But, of course, this is a completely different lift than the one we are used to on our own van, and we have no clue as to how one might "go manual." Chris is still stuck. We are no longer concerned about missing the party -- that is a given -- but amid the jokes about getting Chris down before winter comes, an edge of genuine worry has begun to set in. Suddenly, I am struck by the idea of creating a ramp from the lift down to the ground. We will bring the mountain to Mohammed. I drag over the 6-foot ramp we have leaning on the side of our garage, and the nurse and I create a rather precarious get-away, the angle of which rivals the perch Chris is currently on for degree of difficulty. Ever game, Chris lets us guide him slowly down. We've done it! Backs are slapped, whoops of triumph ring through the air. We have conquered the unconquerable! We are unstoppable! This is one of those "oddly uplifting" (no pun intended) moments of glory, of overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles, that brings a deep and genuine satisfaction. The fact that the obstacles were actually created by our very circumstances is irrelevant. Victory is ours. We wheel into the house, call our friends to say we won't be able to make the party, and regale each other with our re-telling of the story we just lived. Then I make us all a stiff drink. After all, we're only normal.

Movie Reviews | Contact Info | Have Your Say | Photo Gallery | Song Lyrics Transcripts | Mailing Lists | Interviews | Other Websites | About Us | Search

|